Interview with Patrick Hopkins, Co-founder of MSH China

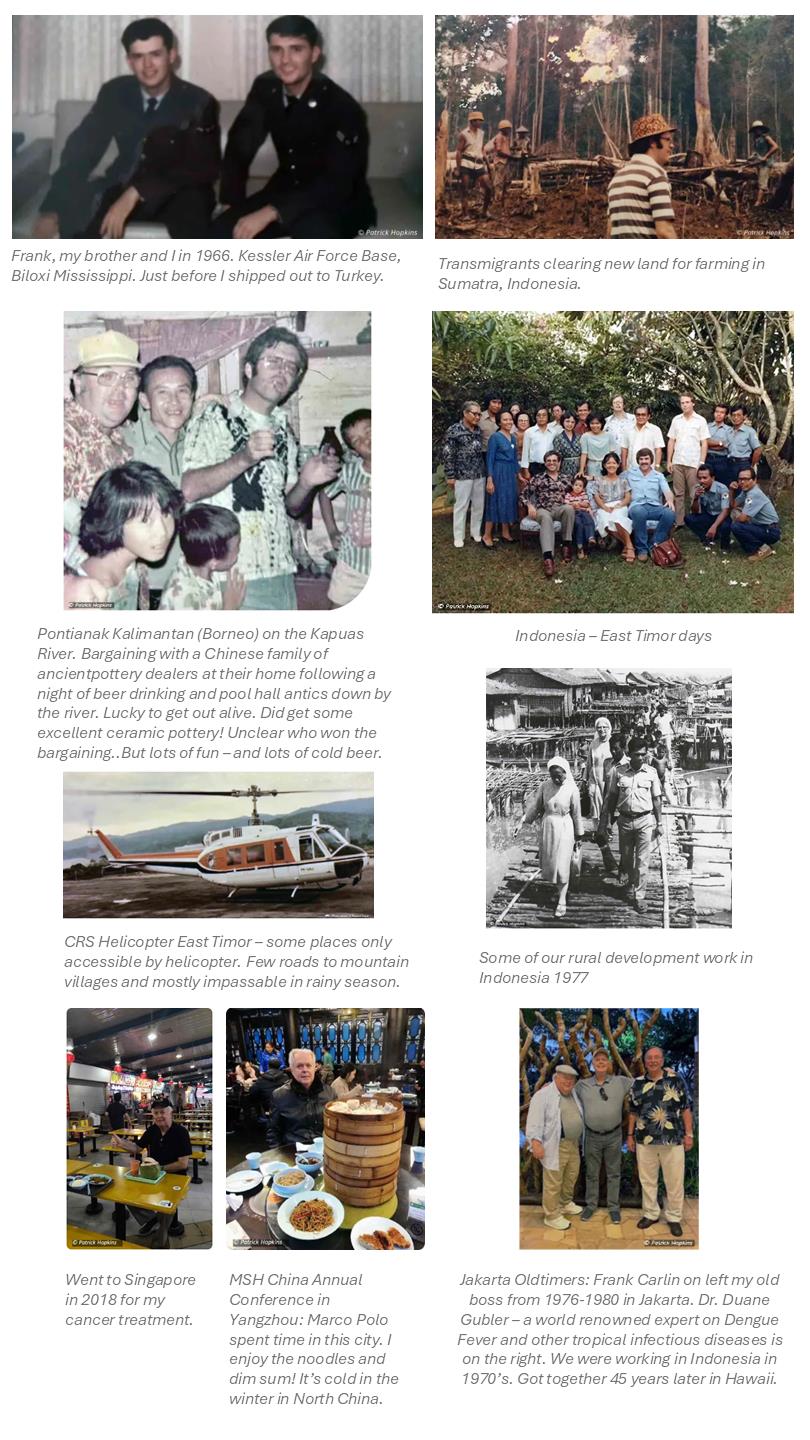

Born in the USA, Patrick Hopkins got to know and love Asia in the 1960s. After his time in the Air Force, he worked for many years for an American non-governmental organization in the hotspots of the world at the time. Later, living in Indonesia, he switched to the financial sector, where he became so successful that years later he founded a successful health insurance service company in Shanghai, which is now internationally successful as MSH China. This interview is a very special personal retrospective and a journey through time with historical dimensions.

Q You were born in the USA. How would you describe your childhood?

Patrick:I was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1947. At the time, Harry Truman was still President of the United States.However, I grew up in a small town in Wisconsin about two hours away from Chicago. My parents moved there when I was about ten years old. It was a very rural place, very close to nature, beautifully situated and with a large lake running through the picturesque landscape. Williams Bay only had 1.500 inhabitants back in 1957 and I remem- ber that many wealthy people from Chicago spent their free time there. In a way, I had the ideal childhood there. I have six siblings and at that time, as a child you were allowed to play outside all the time, you just had to be home for lunch. It was normal back then and nobody worried.

Q There were big cultural differences between the Midwest and the East Coast in the 1950s.

Patrick:When I was 14, we moved again because my father was promoted from regional sales manager to vice president of sales and marketing at the company’s headquarters. This time we moved to Newtown Connecticut, about an hour away from New York City. It was a big move because there were big cultural differences between the Midwest and the East Coast. While Wisconsin was still considered a fairly young region at the time, having only been settled a hundred years earli-er, the East Coast was already much more mixed. As Catholics, we were an absolute minority in this town of 1.500 people in Wisconsin, while in Newtown, Connecticut there were many religions including Catholics. In addition, the immigrants from Wisconsin mainly had roots in north-west Europe – mainly Swedes and Germans who had fled to the USA after the failed revolution of 1848.

In New York City and the surrounding area, on the other hand, there was a real ‘melting pot’ of different cultures: Italians, Greeks, Syrians, Lebanese, Jews and many Eastern Europeans. Whereas in our small town in Wisconsin, practically everyone knew everyone else, it was a small microcosm. It was very different in Connecticut, much more mixed. The area was also much more affluent. So that’s where I spent my high school years. But if someone asks me where I come from, where I have my roots and where the foundation for my values was laid, then I say: Williams Bay in Wisconsin.

Q So was the move to Connecticut a culture shock for you?

Patrick: I wouldn’t put it that drastically, everything was just different. Especially given the fact that I was a teenager com- ing to a new school. I missed my friends and in the big city it was a bit harder for me to make new friends. But it was okay. I finally graduated from high school in 1965 and went to college. However, I was far too immature for college. I didn’t take it all seriously. But at least I was smart enough to recognise my own weaknesses and strengths. So I dropped out of college because I knew it was a waste of my time and my parents’ money.

Q At the time, the Vietnam War was already going on and many young men were drafted. They also ended up in the army after dropping out of college.

Patrick:When I was in high school, it really wasn’t an issue at all. I never heard anyone talk about it. Even in my first term at college, in September 1965, the war wasn’t discussed. It only be- came critical at the beginning of 1967.

The chances of me being drafted for the Vietnam War were close to 90 per cent.

It was like this back then: if you went to college, there was a deferment for mili- tary service for students. So you weren’t drafted if you attended a university. That was very unfair. You know, it’s always the same, the rich people are always fa-voured and live in safety. We had already experienced this in our civil war in the 1860s. That too was a war of the rich and the struggle of the poor. They fought for the abolition of slavery, even though ulti- mately only a very, very small percentage of people in the South owned slaves.

In my youth, it was normal for young school leavers to have no idea what to do after graduation. As a young man, you often just went into military service and grew up there. And that’s how I end- ed up in the Air Force when I dropped out of college. There was definitely a calculation behind it. In the meantime, more and more young men were being drafted into the Vietnam War. At the time, the likelihood of this happening was around 80 to 90 per cent.

I had always been good at analysing situations and came to the conclusion that I too would end up in Vietnam if I didn’t do something. I thought to myself that even if nothing bad happened to me, that is, if nobody shot at me or I didn’t have to shoot at anybody, it would be a complete waste of two years of my life. So the alternative was to enlist in the Air Force, which could choose its own people and didn’t draft conscripts. The prerequisite was a series of entrance exams and various tests in which you had to do well. It was possible to apply for certain areas of operation. In my case, these were all areas in which I primarily did administrative work.

Q Did this ensure that you didn’t have to go to Vietnam?

Patrick:No, there was no 100 per cent certainty. But it would mean that I would be sitting on a base doing something productive. In fact, I did well and was accepted into the Air Force. My technical job was called Morse code intercept operator, because back then the military still used Morse code. Our job was to intercept communications, and I would listen to the Morse code and just transcribe it, like a monkey sitting in an air-conditioned office. It was basically shift work, so sometimes during the day and sometimes at night, and it was actually an interesting job.

I was a 19-year-old kid who was suddenly having completely new experiences far away from home.

After nine months of technical training, they sent me and my mates to Turkey for 18 months for our first overseas assign- ment. I was deployed to a listening base about three hours away from Istanbul on the Marmara Sea. That time was very for- mative for me. I found it fascinating and exciting to get to know a different culture.

After this year and a half, I was trans- ferred to Okinawa in Japan to work on a listening base as well. That was in 1968 and in fact the Okinawa archipelago had not yet been returned to Japan by the USA and was occupied by the US army. Okinawa was not returned to Japan until 1971.

Q From Turkey to Japan, so you had your first contact with East Asian culture?

Patrick:Yes, that’s how I came to Asia. Japan was another really interesting ex- perience. I even learnt a bit of Japanese. I finally finished my military service in 1970 and went back to college in the United States. I chose Connecticut be- cause the tuition at this state university was comparatively low. I simply took every course that interested me. These included courses on the Middle East and Southeast Asian history. I just col- lected credits because I knew I wouldn’t stay at this college until I graduated.

Q What was your actual educational goal?

Patrick:I actually wanted to be a foreign correspondent for the New York Times or something similar. So I applied to two journalism schools. One was at Sofia University in Tokyo. And the other was at the University of the Philippines in Manila. And I was actually accepted at both schools! However, the political situation in the Philippines was a bit too dicey for me. The dictator Marcos was in power, he hadn’t declared martial law yet, but I was afraid that something like that could happen. Due to my military service and my time at Connecticut College, I already felt four years behind when I started my studies at the Catho- lic university, Sofia University in Tokyo.

Unfortunately, I discovered that the university had just closed its journalism programme. So I switched to East Asian Studies, because Japanese culture is fascinating. I ended up doing a Master’s degree in East Asian Studies. I was 28 years old at the time. The only ques- tion was: what the hell do I do now?

I definitely had a decisive advantage: back then, there weren’t many people interested in East Asian culture and it was rare to find an American with a very good command of Japanese. I would have loved to pursue a university career. If I had seen a way to become a professor, I probably would have stayed to do a PhD because I loved living in Japan. However, I was smart enoughto realise that my chances of making a career as a university professor in Japan were slim.

I didn’t want to be a small cog in the wheel – without any signifi- cant influence.

Q What happened next?

Patrick: With my specialised knowledge, I had two options: I could either work for an international non-govern- mental organisation (NGO) or for the US government. At the time, they were looking for people like me with these skills. I got as far as a third interview, but realised that this job wasn’t right for me. I would have been a small cog in the wheel – without any significant influence. Although the job would have paid well, it didn’t appeal to me to just sit there and listen to Japanese, trans- late documents and analyse them – it didn’t seem like something I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

So I ended up applying to a non-govern- mental organisation, the Catholic Relief Service. This is comparable to Caritas in Germany. It is the official overseas aid and development programme of the Catholic Church in the USA. It wasn’t nearly as well paid as the government jobs, but it was about helping to save children. I had the choice of being as- signed to the Philippines or Indonesia. I opted for the latter. I found the Indone- sian culture more exciting, the country seemed even more exotic to me than the Philippines. Indonesia was a very poor country back then. There had been an anti-communist purge in the late 1960s and the Dutch colonial rulers had left the country in a poor state. Our task was to implement mother-child nu- trition programmes for malnourished children and mothers. We also carried out income generation projects in rural areas, bred ducks and chickens and produced agricultural products.

Q Has this work had an impact on how you see people in general? I can only imagine that the sight of all this pov- erty and starving children triggers something in you.

Patrick:Well, that wasn’t the worst thing about working there. You just did your job and tried to help as much as you could. We worked through local or- ganisations that ran the actual feeding programmes. So we were more the ad- ministrators of these programmes and made sure that the funding and food got to where it needed to go. It was also our job to empower the aid organisa- tions on the ground so that they could continue to work without our help at some point. All in all, it was a very ful- filling and meaningful task. There was really terrible suffering in East Timor. Most people no longer remember that.

Q You mean the East Timor conflict in 1975, which resulted in one of the biggest famines in modern history?

Patrick: Yes, there was a lot of suffering, great suffering. The Portuguese colonial rulers left practically overnight during the uprising and left behind a mess. The Indonesian military was very nervous about the uncontrolled situation. The territory was annexed by Indonesia. And countless people died, everything got out of control. Virtually no aid organisations were allowed in. But the CRS I was working for had built up a very good reputation as a partner.

Coincidentally the head of Indonesia Military Intelligence, Gen. Benny Muradani, was a Catholic. He was a tough and no nonsense officer. But so was my Boss Frank Carlin a former US Marine. Frank gained General Murdani’s respect and CRS was granted access to East Timor along with the ICRC. Frank ran the pro- gram in East Timor and I backstopped the program logistically. We signed contracts for barges and landing craft to bring in tonnes of food and medicine. Purchased trucks and rented helicopters. Quite an elaborate operation. Saved tens of thousands of lives.

But I was very satisfied because I had done my part to help the local people. When my work was done, I wrote a con- cept for a development programme to get these people back on their feet and provide them with some income.

Q What was your next stop?

Patrick:I worked for the CRS in Asia until 1984. During this time, I got to know and love the fascinating Asian culture better. In 1982, I came to Islamabad in Pakistan, where the CRS was helping Afghan refugees who had left the country because of the Soviet invasion. I was chosen because I had already worked with people of Muslim origin. When we arrived, however, we realised that the Pakistanis had already done a very good job. There were 13 refugee camps, each with an aid or- ganisation assigned to it. That was very clever and effective. It is often the case that 16 different NGOs look after one refugee camp.

So my job there was essentially to pro- vide support, because the camps were already assigned to the other organisa- tions. I worked with an NGO called the ‘Austrian Relief Committee for Afghan Refugees’. They mainly support the Haz- ara ethnic group, a Shiite ethnic group who are a kind of descendant of the Mongols and look more like them than the other Afghan population groups. I also supported the Agha Khan Founda- tion in northern Pakistan in the foothills of the Himalayas and I co-operated with the Catholic diocese in Pakistan. That was a very interesting time.

But at some point the Catholic relief organisation changed. When I started working at the CRS, people like me, who were programme managers or foreign representatives of the Catholic Church, basically had to be Catholic. So I really had a Catholic touch.

Then in the 80s they changed their philosophy and the church tried to get more lay people involved because it was so dependent on non-clergy be- cause not many people want to become priests by choice. When my previous boss as Asian Regional Director for CRS was replaced in 1984, I knew it was time to leave. The new Asian Regional Di- rector was a priest that I had a difficult time dealing with during the East Timor programme. We did not get along. I knew it was time to move on.

In addition, the world had changed a lot. The days when developing coun- tries needed Western aid organisations were over and local education systems had improved.

Q But you didn’t go back to the USA.

Patrick:Exactly, I wanted to stay in Asia. My roots were in Asia. Initially, I worked as a contractor for the US Agen- cy for International Development, which had a lot of projects in Pakistan. Ultimately, however, it was mainly about boosting the Pakistani military, there were no humanitarian tasks in the true sense. That certainly put a strain on me. I got on well with the government officials. However, I found many of the US advisors to be very arrogant; they very often turned up their noses at the Pakistanis and claimed, for example, that the Pakistani engineers were not doing a good job. But they were very good. At the end of the day, this job was about supporting the Saudis and the Pakistanis in the war in Afghanistan to fight the Russians. I found myself becoming cynical and feeling that the big Western aid organisations were actually political organisations, even if they never admit- ted it themselves.

If you’re in sales,you should be a good listener.

That was not what I wanted to do in my life. I had an offer to work for the Asian Development Bank in Manila, with a great salary, a big house, a nice pension and so on. But I would have been a small part in a big bureaucratic machine. And I’m just not the type of person who would thrive in a bureau- cracy. I’m also not good at pushing myself to the fore. When you work in a bureaucracy, you have to socialise and somehow stand out and do a lot of things. And that wasn’t what I was good at.

As luck would have it, I reconnected with a friend from my time at CRS whose wife worked for UNICEF in Jakarta. My friend worked for a financial services company headquartered in Vienna. Its main niche was US diplomats who travelled to em- bassies around the world. They used the broker’s financial products. He advised me to work for this company.

Q However, you had no experience and had not studied economics. Why did you have the confidence to become a financial advisor?

Patrick: It’s true, I didn’t have that. People also thought I was crazy to start my own business - without a fixed in- come, without money for an office and without a travel and expense account. But I knew that if you work in sales, you need to be a good listener. In essence, it’s about finding out what the other person needs, what their needs are and how you can help fulfil those needs.

In the end, it turned out that the US diplomats were not the greatest target group, but I increasingly came into con- tact with the international schools and the teachers employed there. These US teachers had fallen out of the US social security system and were therefore no longer entitled to a US pension. So there was a gap. However, it was important for them to be covered. In addition, it was often the case that mar- ried teacher couples were employed so that the schools only had to pay for one house or one flat for two people.

This meant that these couples could live on one salary and invest the other salary in savings - or in financial products. I set up almost 1,000 savings plans for these teachers. They were paying in between 800 and 2,000 US dollars a month, and with around 1,000 people that adds up to a lot of commission. And that’s how I got into the insurance business, because the schools needed insurance for their staff. I did that for a good 16 years.

What’s more, I didn’t even have to work all year round because the teachers were usually on home leave in the summer months and over Christmas.

Q Basically, you were then financially secure and didn’t have to continue working?

Patrick:Yes, but I was 52 years old at the time, I had lived in Jakarta and Manila. And I travelled to China. Once I was in Beijing, another time in Shanghai, another time in Osaka, another time in Tokyo, then I flew to Jakarta. So I visited all my schools on my round trips. There were two problems. Firstly, I was trav- elling 50 percent of the time. So what kind of social life did I have? It was okay, I didn’t have any children. The other thing was that I kept meeting the same people, who I enjoyed working with, but there was no challenge anymore.

In the very first year of working with MSH, we were able to reduce the claims of insured per- sons by 25 per cent with- out any restrictions.

So I made a decision. I said to myself: why don’t I go to Shanghai, a big city, in- stead of travelling all over Asia, and try to develop the market in a metropolis with a population of 20 million at that time. I had never worked with multina- tionals before. But I knew that if I tried it, I would need someone on the ground to guide me. Otherwise I wouldn’t stand a chance. So I hired Celine, the current head of MSH China. The rest is history.

Q A very successful story. How did this company actually become MSH China? How did the collaboration come about?

Patrick:I met the founder of MSH, Pierre Donnersberg, in 2007. MSH had a lot of customers in China, but no way to manage the insurance claims. They were losing a lot of money as a result. We, on the other hand, had 45 employees. So MSH hired us to help them with the medical management of their existing clients. So we were just contractors, if you like. In the first year alone, we were able to reduce claims by 25 per cent. Simply because the medical management team negotiated with the hospitals. It had no impact on the customers. It’s easy to reduce or simply refuse claims, but we didn’t want to do that. All we did was work with the hospitals to make sure the bills were correct - and as long as they know someone is looking, you can negotiate.

If you want to be suc- cessful in China, you have to be humble.

At one point Pierre asked me if we would also consider a takeover by MSH. I said: Well, why not? We didn’t want to sell, but we should be open to everything.

Around 2007, MSH was in the process of positioning itself internationally and growing through acquisitions abroad. So Pierre came to us in Shanghai in 2007 with a few others from MSH. At the time, he mainly spoke French, which I didn’t speak. But Pierre has a special talent: he can see people without the need for intensive verbal communication. That’s why he knew that we were the kind of people he wanted to work with. After about six months of negotiations, we came to an agreement. But then the financial crisis hit in 2008 and the sales process stalled.

In 2009, the deal finally materialised after all. In 2011 MSH owned 80% of MSH China. We still had 20%. We sold the last 20% of MSH China to a Chinese buyer in 2017. Celine and I decided to continue working for the company and so far we are still enjoying it.

Q I once heard that in China, 50 per cent of a foreign company must be owned by a Chinese investor.

Patrick:No, there is something called a ‘wholly-owned foreign company’. So you can set up a company that is 100 per cent owned by foreigners. In the course of my life, I have made a lot of unfortunate decisions. But I made a smart decision at the beginning of the China business: I gave this company a Chinese face, not a Western face. People know that I was the founder. But I was never the one at the top.

Q So you kind of stepped back. Was that because of your NGO back- ground?

Patrick:No, not that. It’s part of my personality that I’m not an outgoing person. I don’t have a big ego and I’m more of an introverted person. And I’m not saying that in a negative way. Be- cause an introvert is only someone who is comfortable with themselves. I like people, but I don’t need my ego to be constantly stroked. But that’s also part of it, I remember my time at Catholic Relief Services.

When I joined Catholic Relief Services in 1976, the philosophy was that our job was not to travel the world and show how great we were by opening a project called Catholic Relief Services. Our job was to work with local institutions and help them develop the relevant skills.

If you want to be successful in China, you have to be humble. I think many Americans think that our way is the best way. Sometimes it’s true, but in the case of China, I don’t think it’s true. We at MSH China have adapted, that has always been my philosophy. We have to adapt to Chinese conditions instead of expecting the Chinese to adapt to our conditions. This is where many Western companies make a mistake.

Q There has always been a certain - partly ideological - rivalry between the USA and China. Has this ever made itself felt in your company?

Patrick:Here in China and Shanghai, there have never been any anti-Amer- ican feelings among the people. Quite the opposite. In America it’s different. There, people are fed propaganda by the secret services. I have noticed that something has changed since 2017, when Trump came to power, especially among young people. Before 2017, it was cool for young people from the West to come to China for a few years to build a life there, and that was encouraged. Apparently China became too successful in the eyes of the Ameri- cans. Maybe the US got scared and saw China as a threat to their global agenda.

Q You worked for an aid organisation for many years - then you switched to the finance and insurance industry. From the outside, the two seem very different.

Patrick: That’s a good point. In fact, we recently discussed exactly that at MSH in Paris - Pierre Donnersberg, Christian Burrus and also Frédéric Grand. I said to Christian: I’m 76 years old, just like Pierre, and we’re still working. Not because we have to, but because I think that what we do has a social benefit. And that’s important to me.

I believe that what we do at MSH has a social benefit.

We also help people with health issues who are not insured with us, if we can somehow - for example, by intervening in a Chinese hospital if someone is in need and has communication difficulties.

Let me give you a case that happened more than ten years ago: one of our customers was travelling on Yellow Mountain, a famous tourist resort in the Chinese province. And then he had a heart attack. This area is not a good place for a heart attack. We pulled out all the stops at the hospi- tals to get this man admitted. At the time, the hospitals wanted cash. We organised an ambulance at the foot of the mountain to take him to the nearest hospital. And this hospital didn’t want to admit him because the people there were sure he wouldn’t survive and they didn’t want to admit someone to die.

So we sent some of our people there with 20,000 dollars in cash and another doctor and the insured was taken to an- other hospital where he received great care. If we hadn’t helped, he would be dead now. That’s for sure. If you don’t do something to help, you will regret it for the rest of your life. Even if this hadn’t been our customer, we would have done it anyway. It’s simply about humanity. When I do something good, I never expect anything in return. Never. Something good will automatically come back. If you do good, good things will happen to you. That is my philosophy, and that is the philosophy of our company management. That’s what I’m most proud of: when people take care of our customers.